In 2017, Deelstra’s path crossed with that of Brahim, a devout Muslim and employee in

the vegetable department at Albert Heijn.

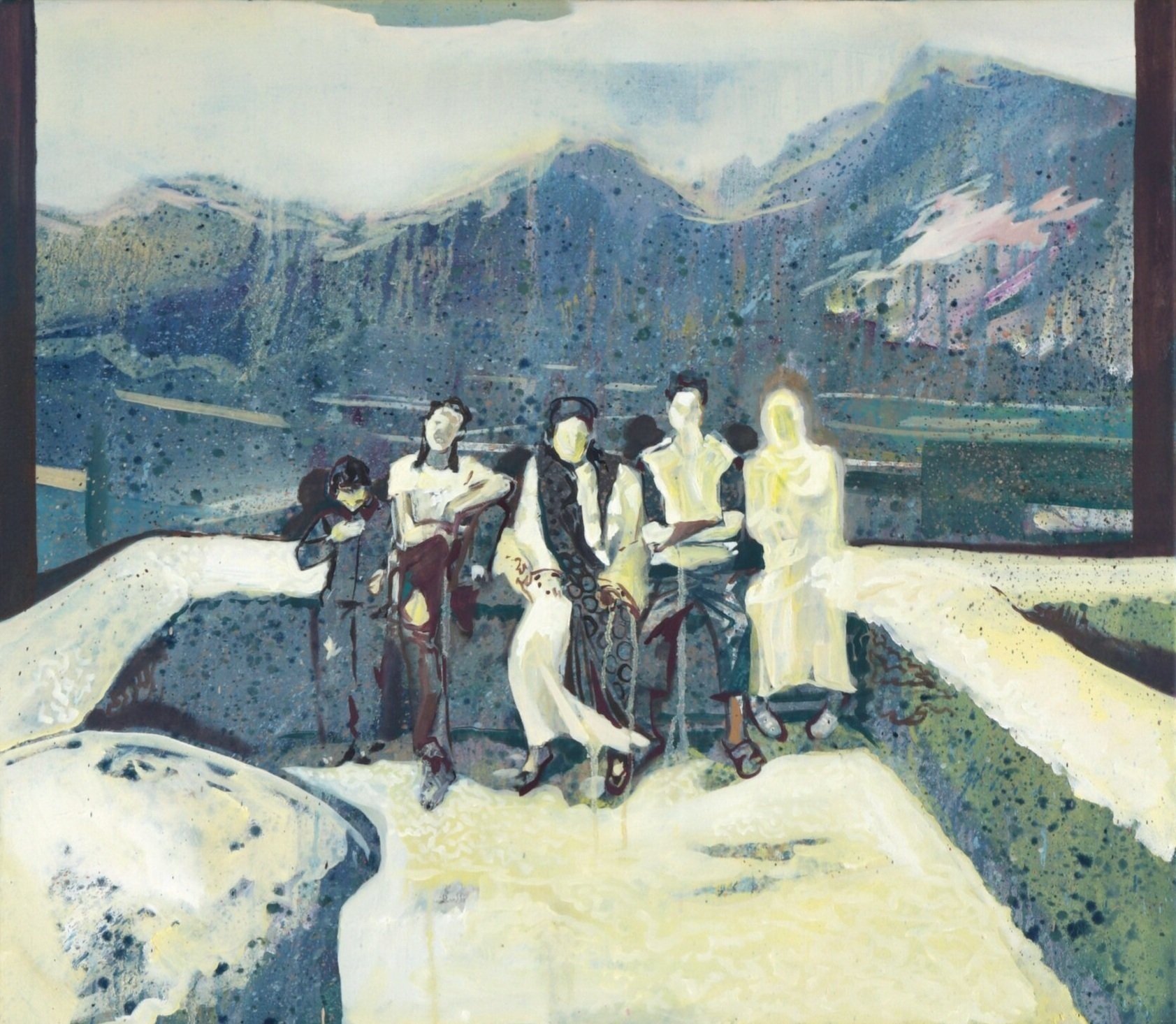

The encounter between Deelstra and Brahim blossomed into a friendship, shaped by their frequent conversations and coffee moments by the vending machine in the store. It is precisely Brahim who plays a crucial role in the creation of the paintings in this meaningful series.

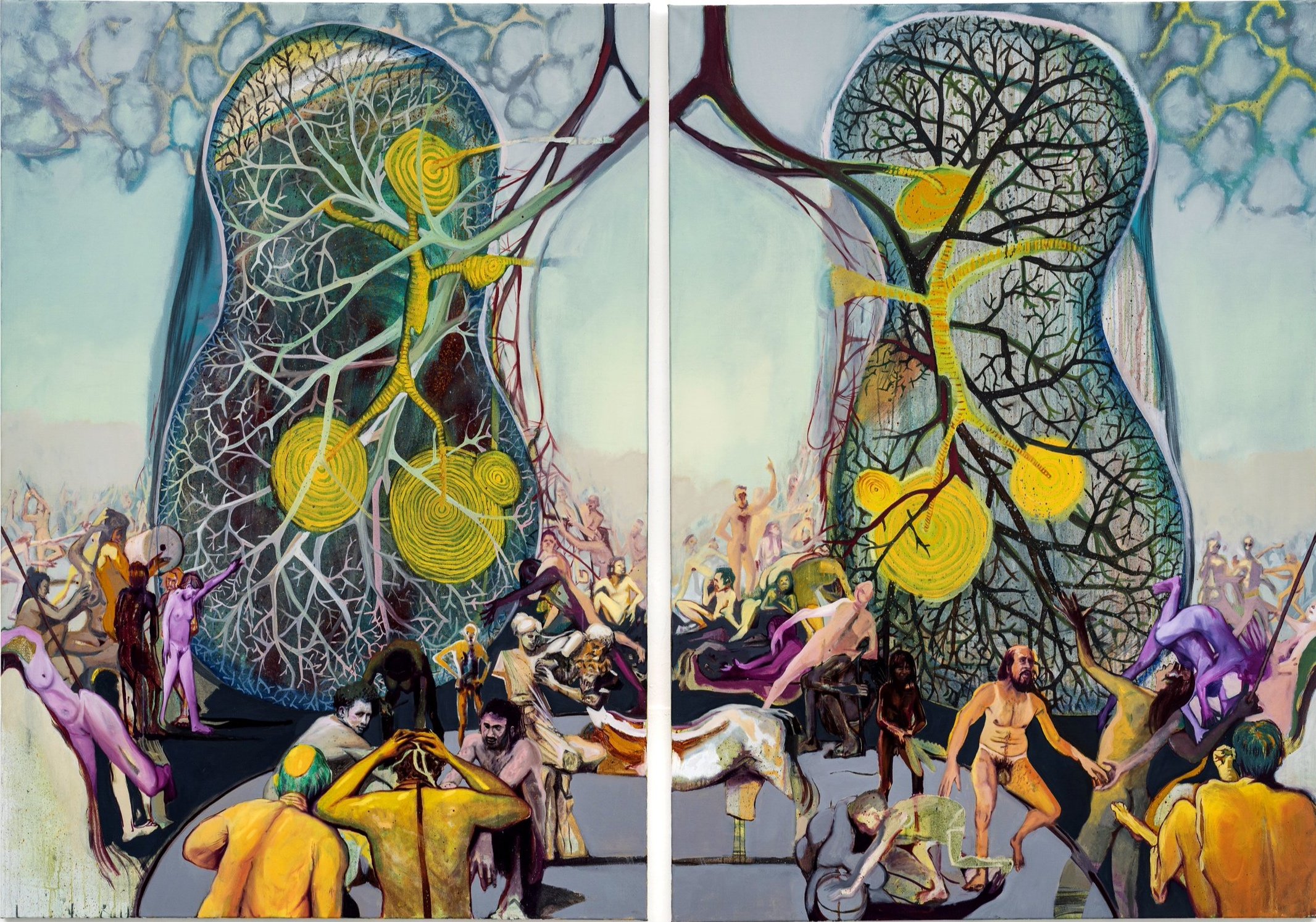

The You in Me (2018) came to light during

a time when the Dutch populist Party for Freedom (PVV) was the second-largest political party in the Netherlands. The political landscape was permeated with a tendency to cast specific population groups in a negative light. The sharpness and inhumanity with which some politicians, even on the highest governmental level, made their statements filled Deelstra with disgust.

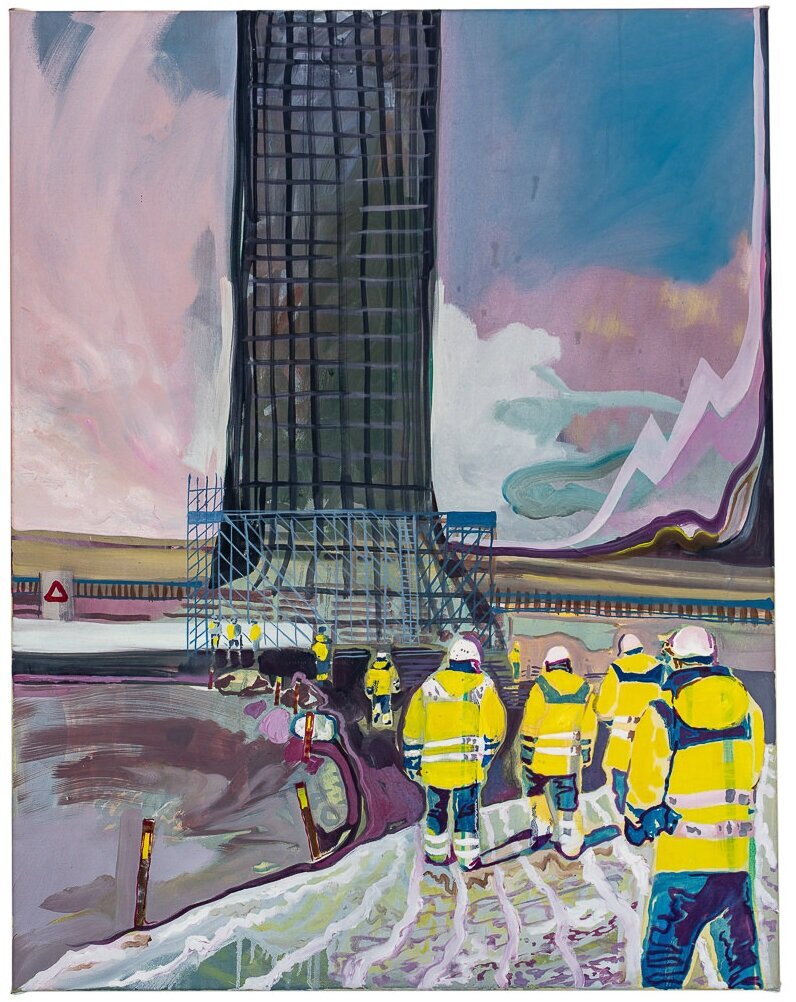

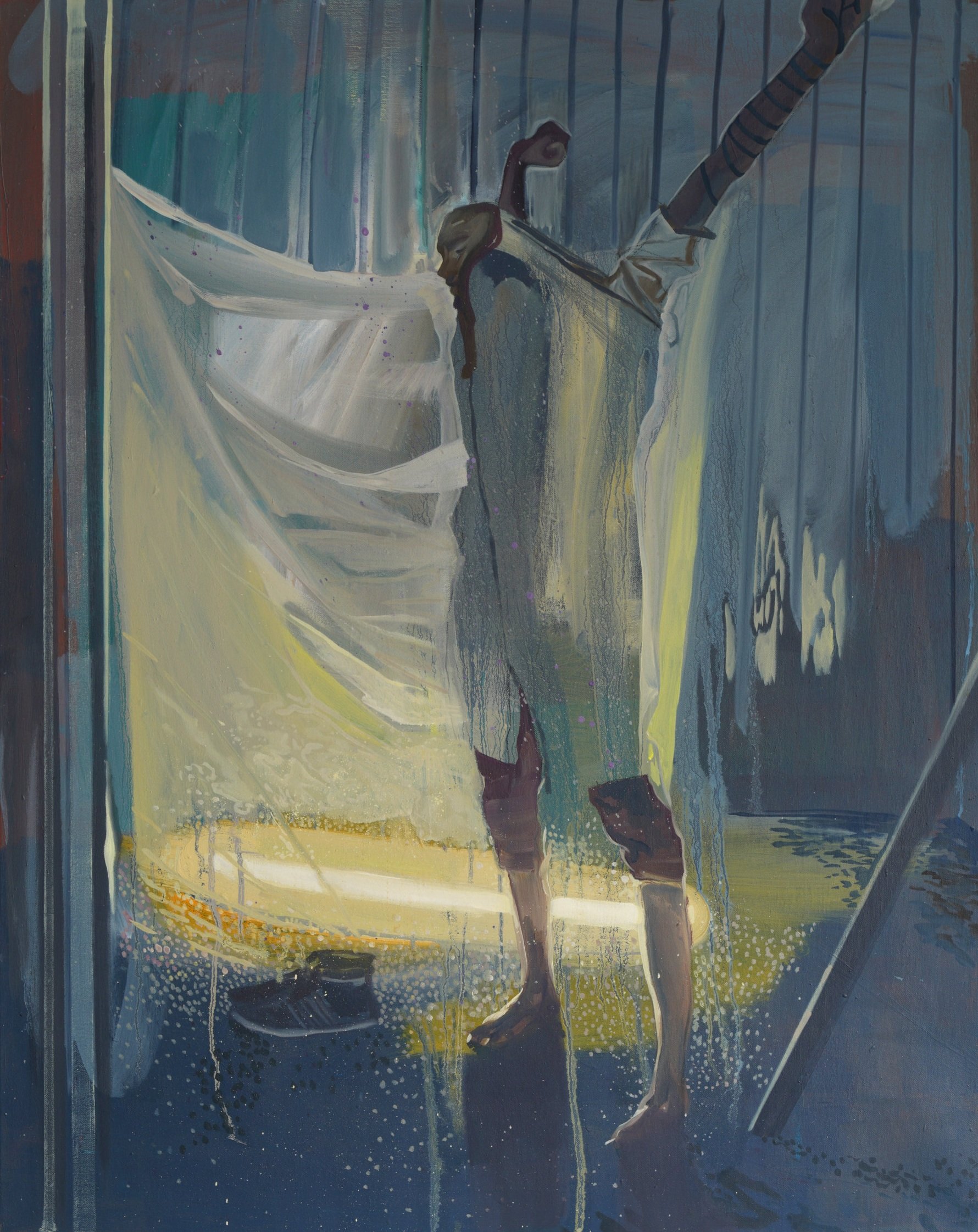

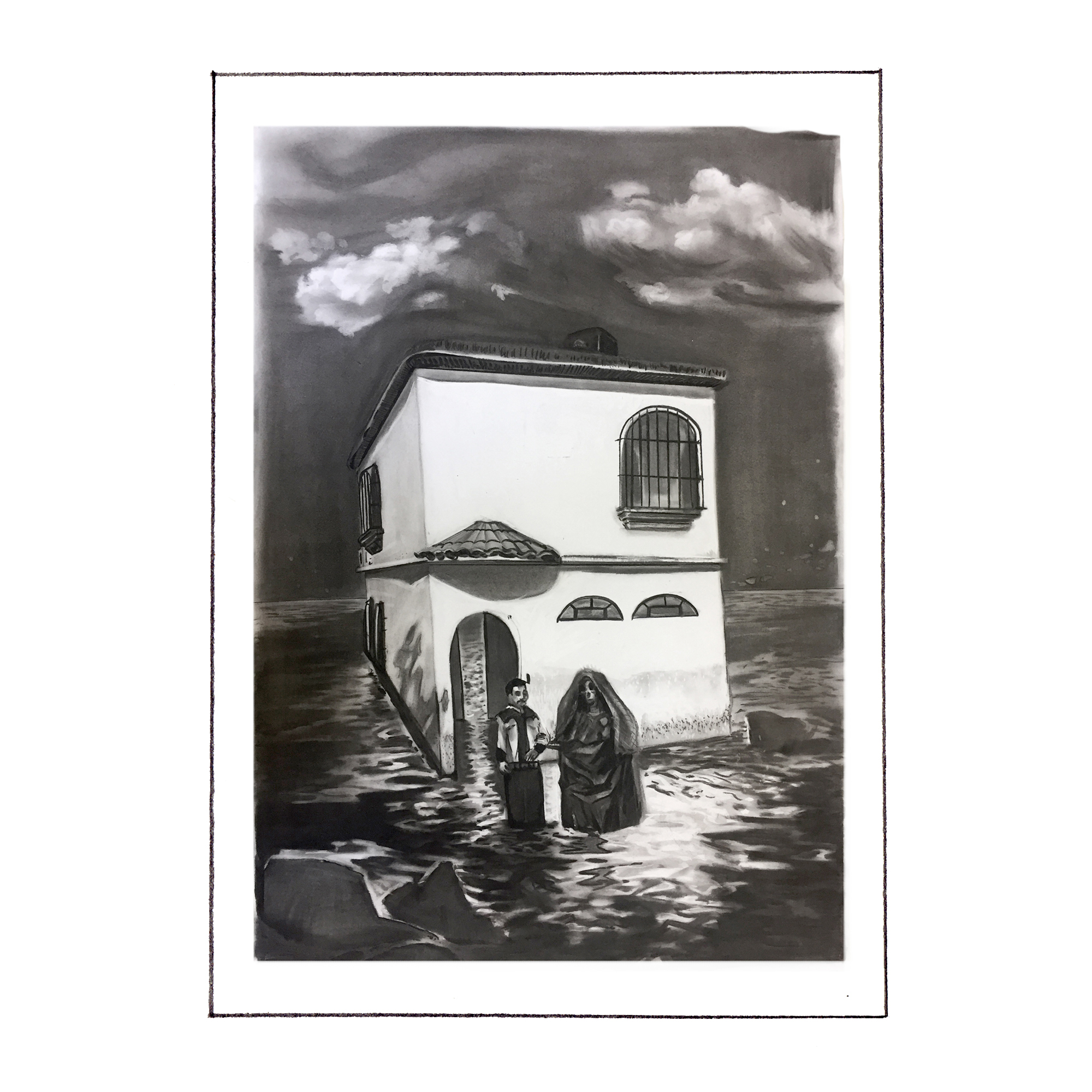

Deelstra longed for a deeper, more nuanced portrayal of identity and its flexibility, especially during times of polarisation. Instead of being dragged into the division, he decided to seek reconciliation. With this goal in mind, he turned to Brahim and proposed shadowing him for a period, aiming to gain a deeper understanding of the complexity of similarities and differences among people. Brahim agreed, and for the following eight months, Deelstra embedded himself in his life.

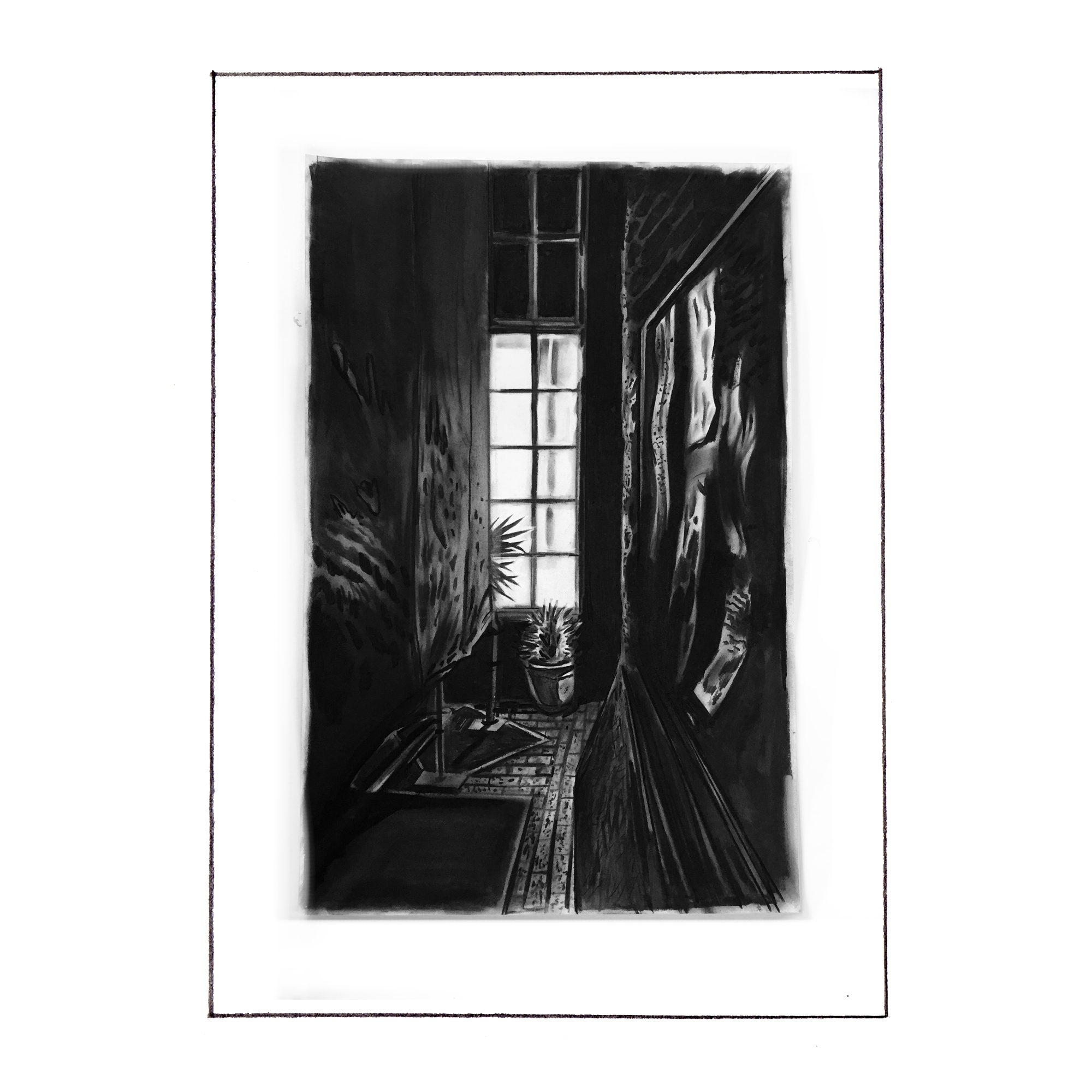

Deelstra: ‘During those months, I often visited his home and got to know his wife and daughter. I followed Brahim closely and immersed myself entirely in his personal world. And all

of this while we both live in Amsterdam, are the same age, both identify as male, live in the same neighbourhood, and shop at the same supermarket: yet our lives are miles apart. With this project, I confronted my own prejudices.’

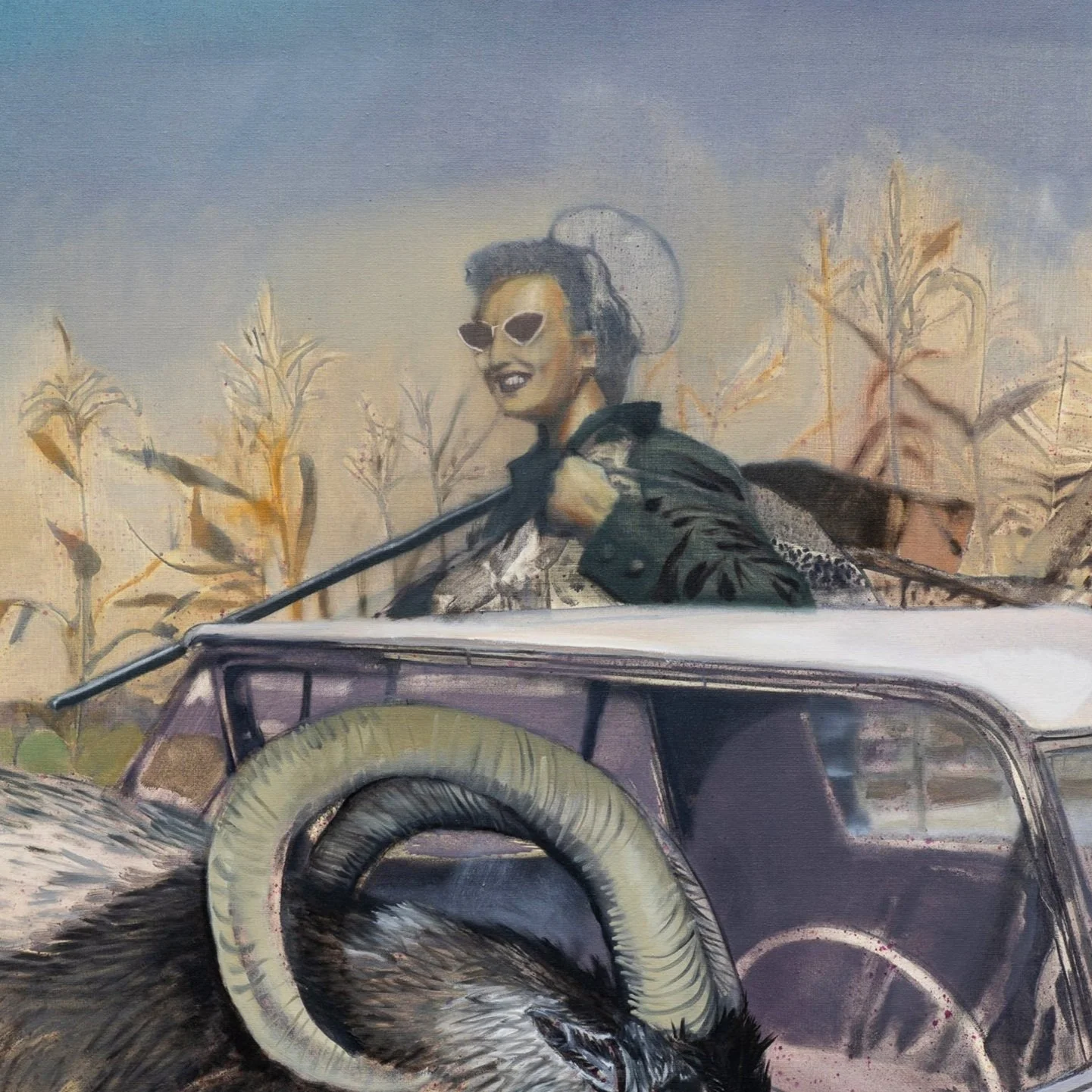

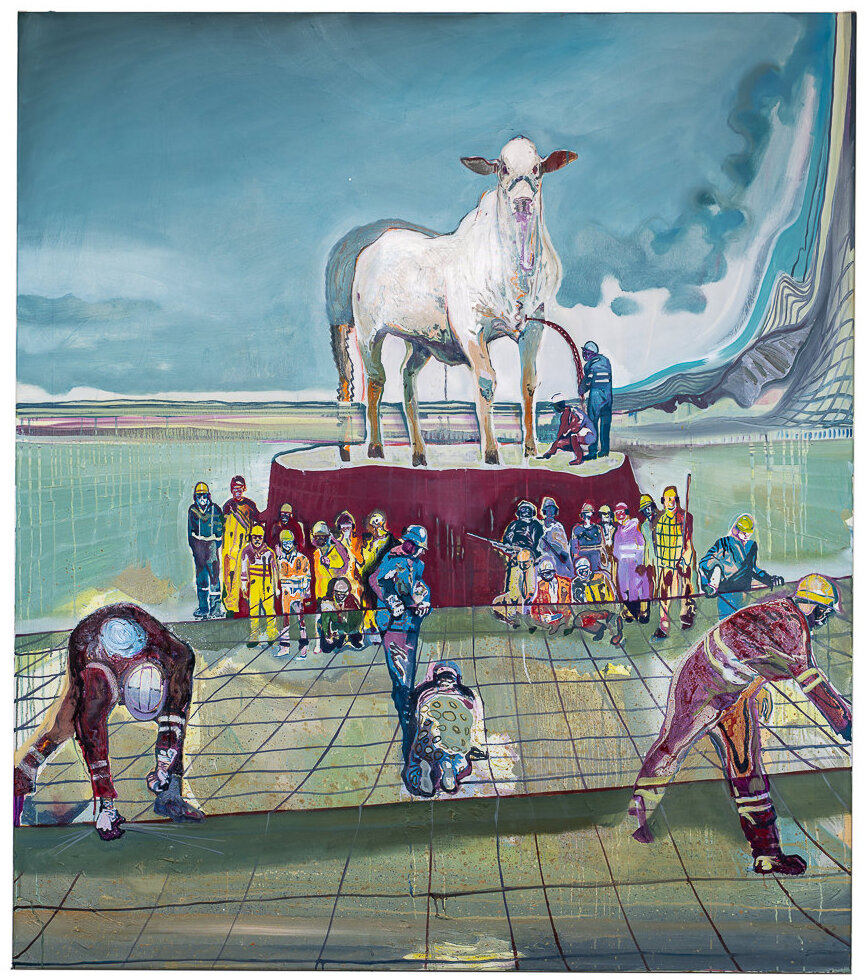

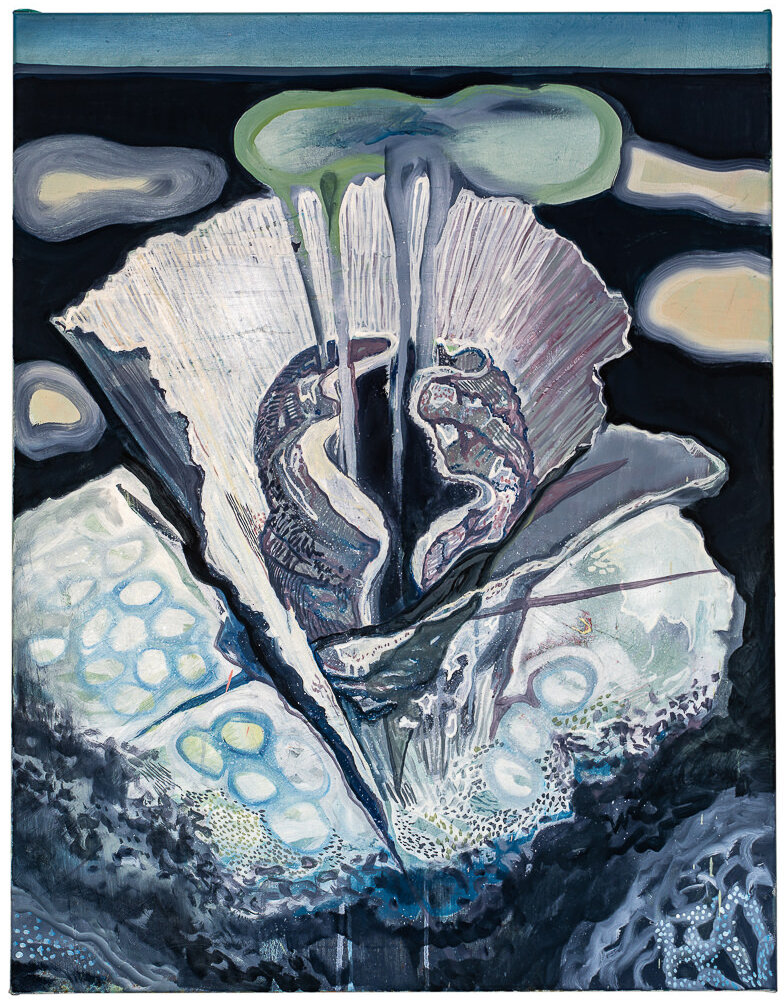

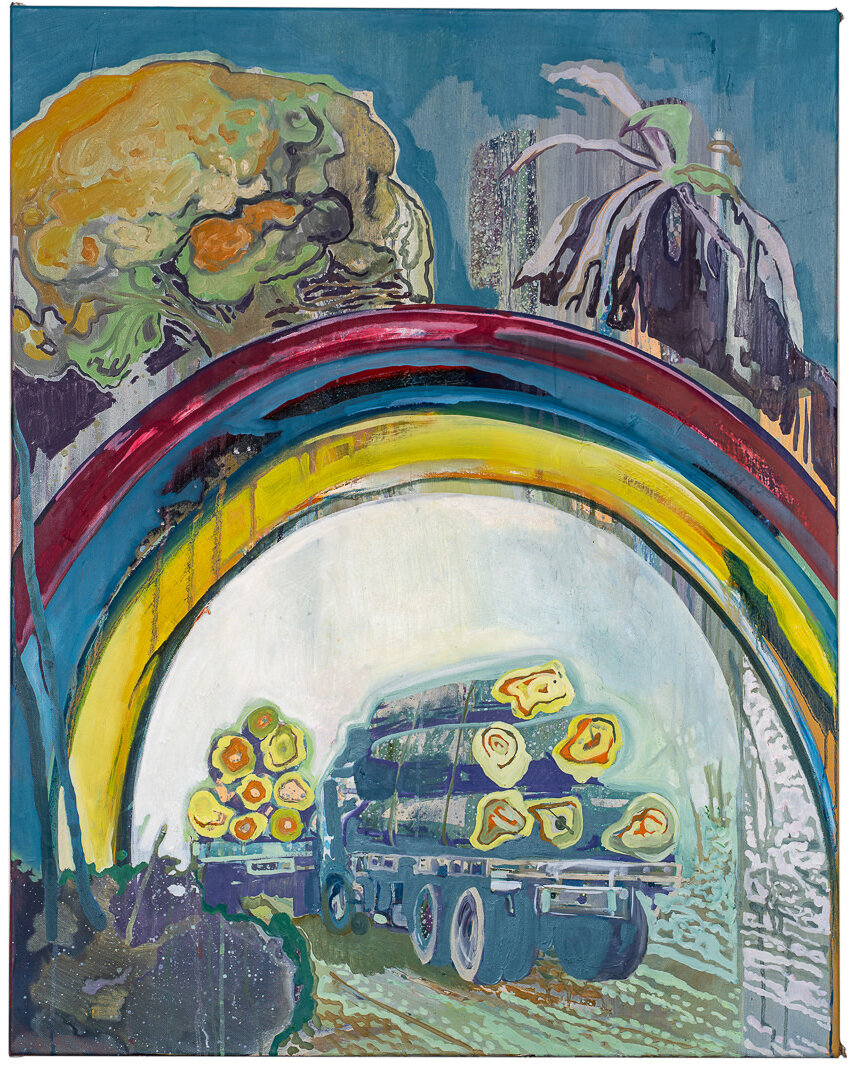

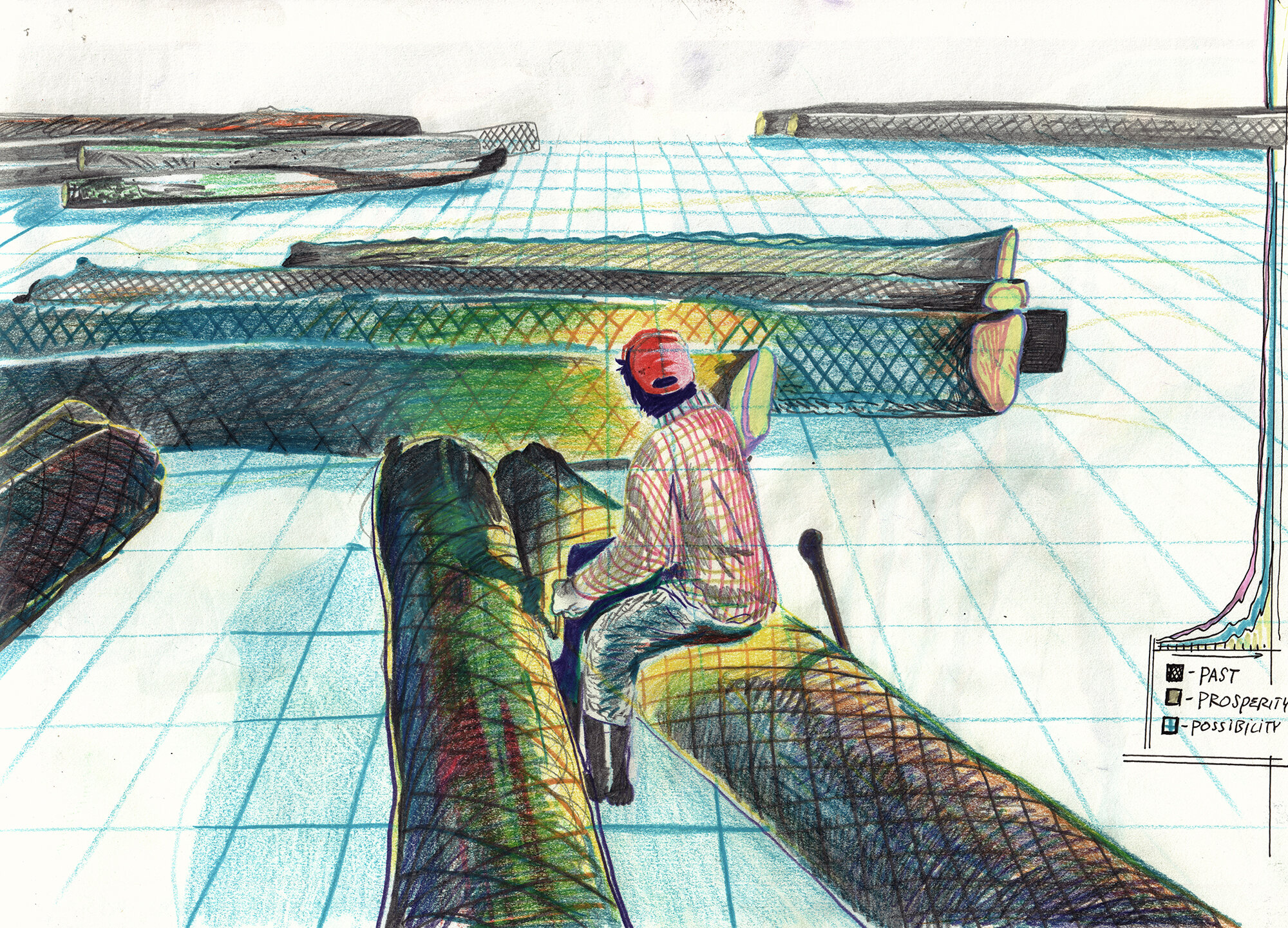

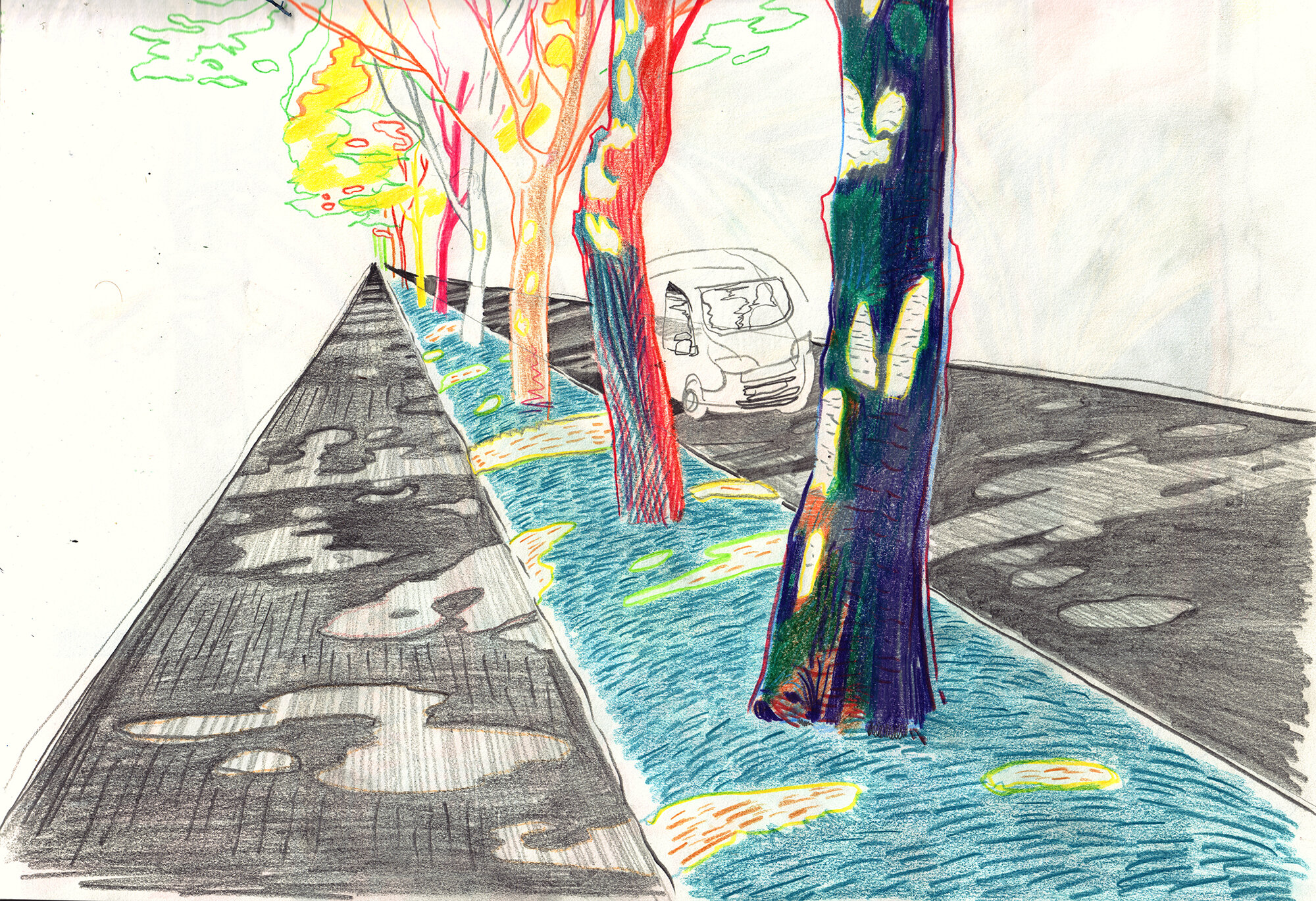

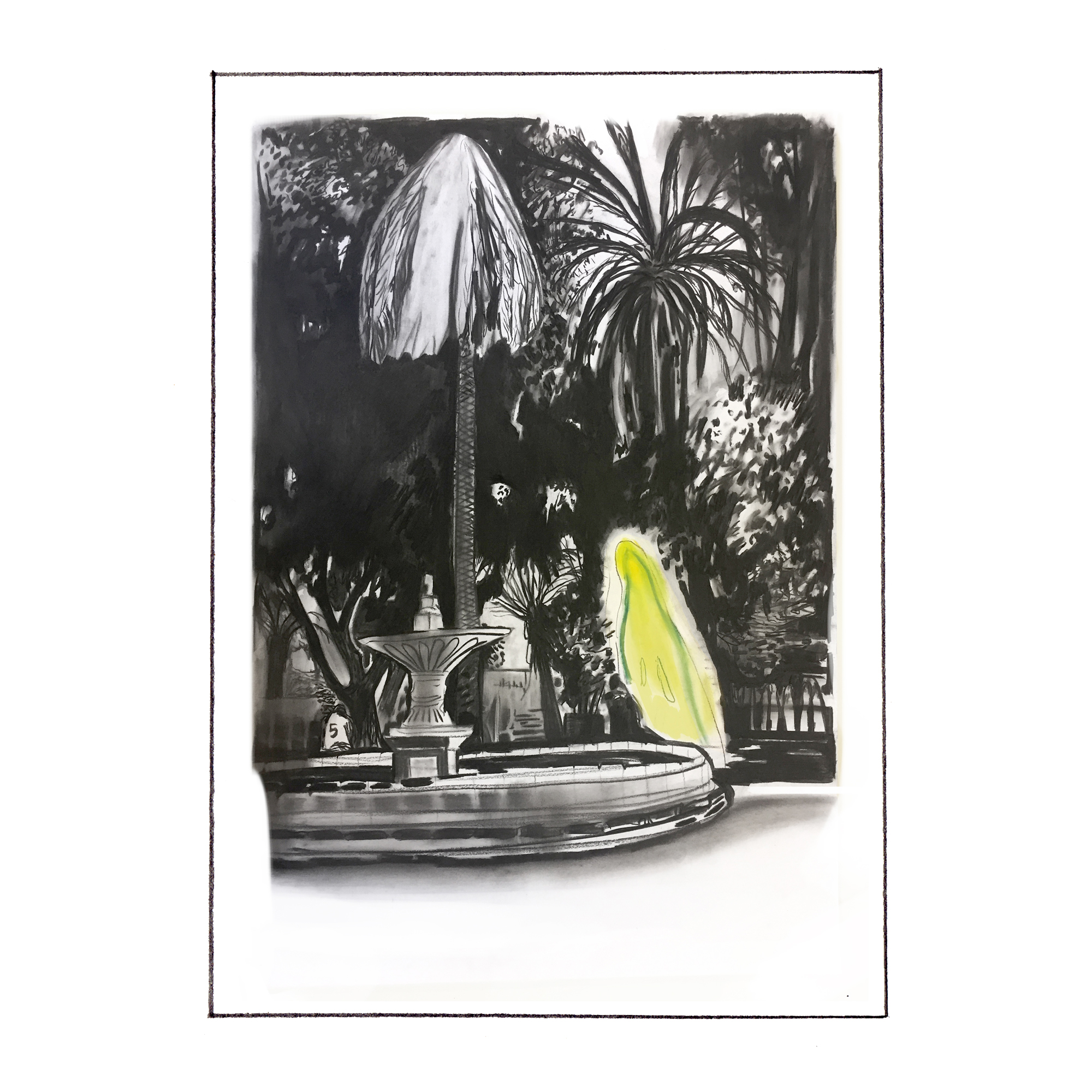

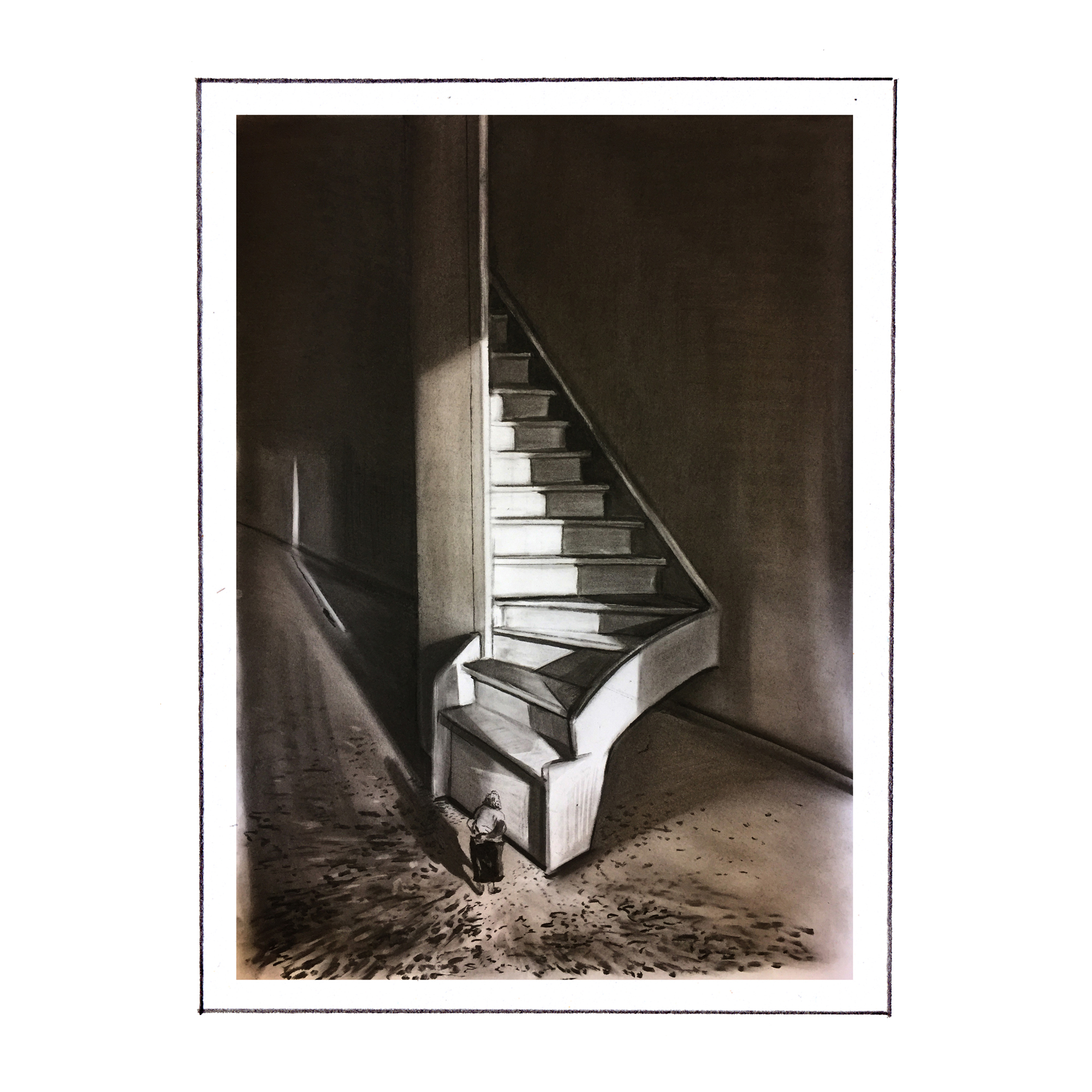

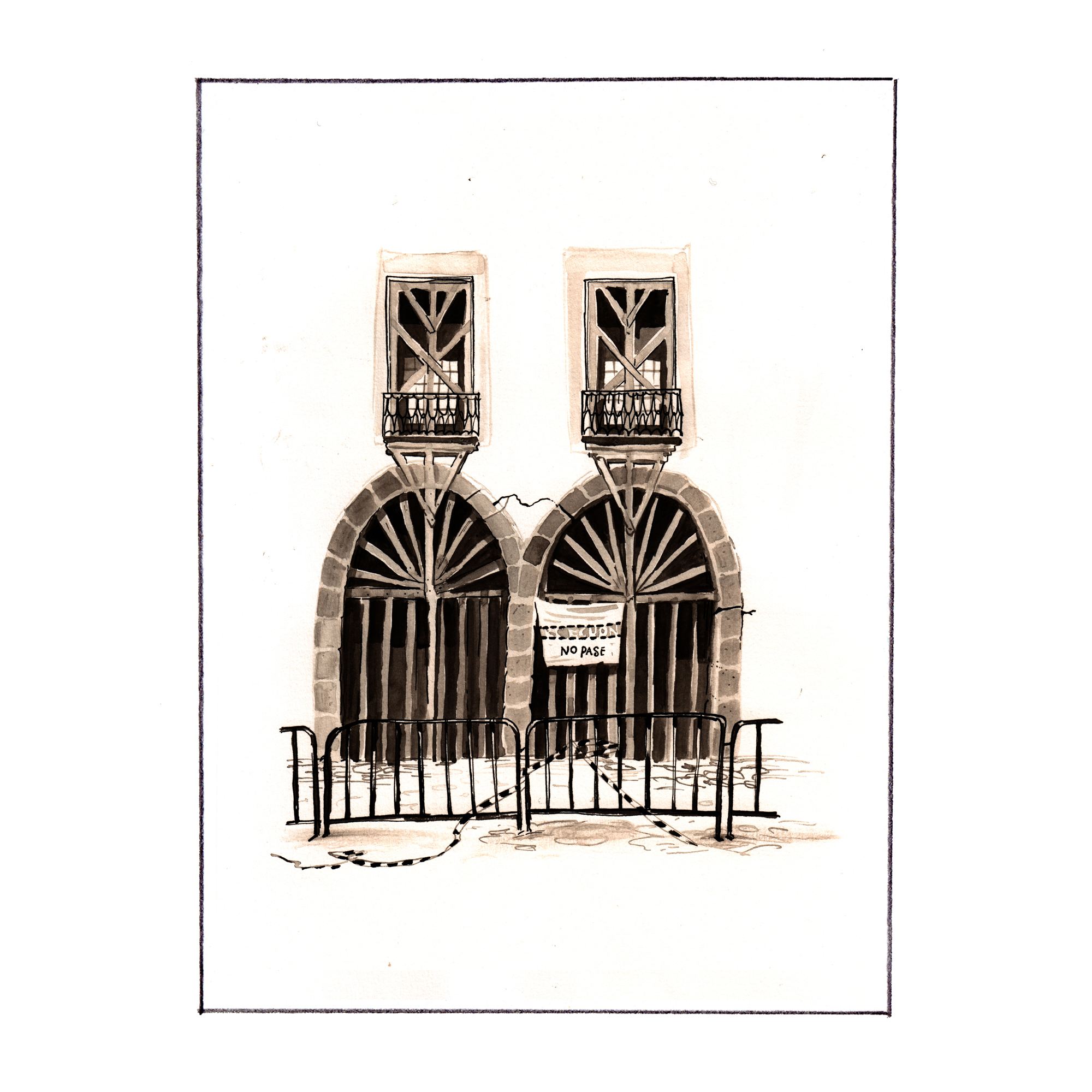

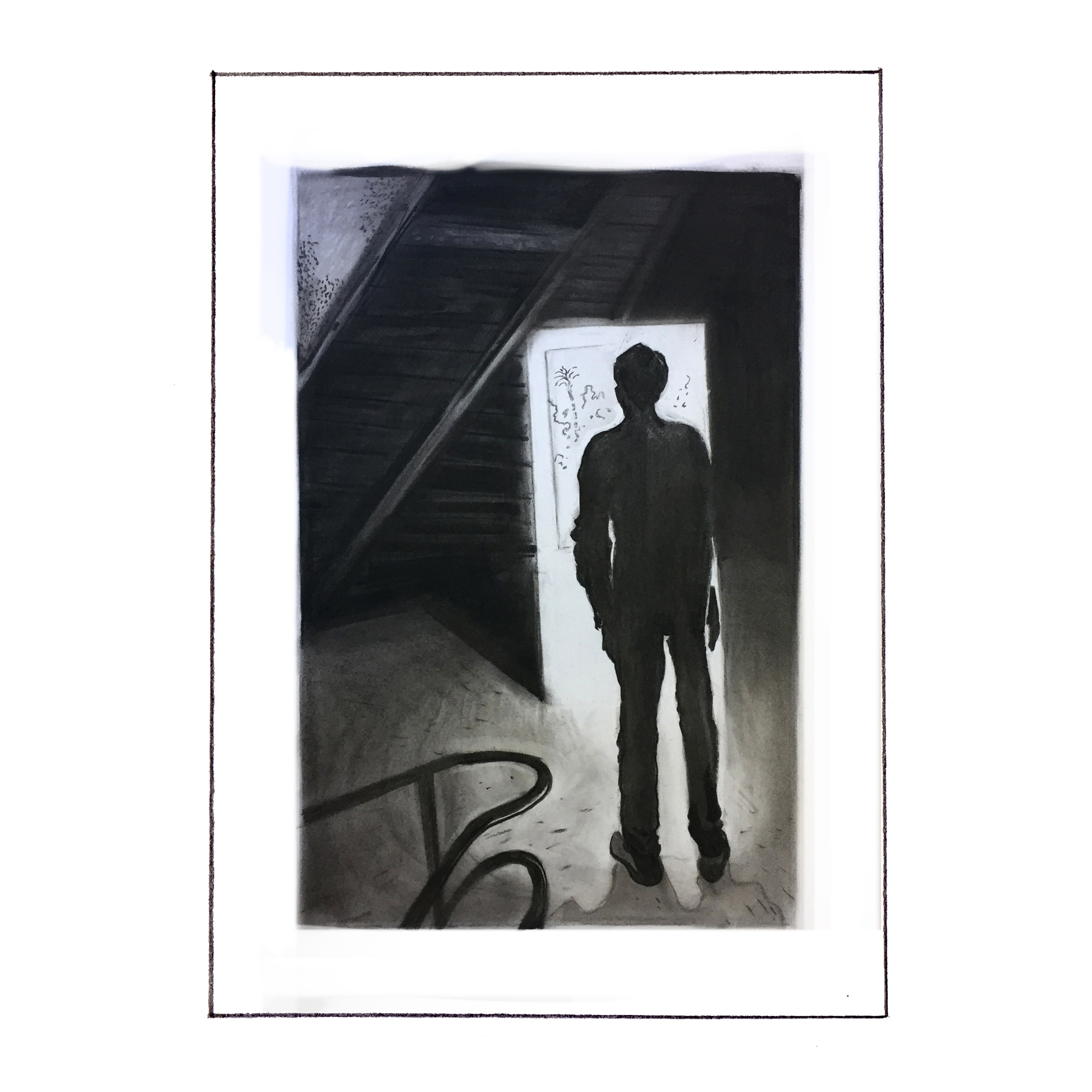

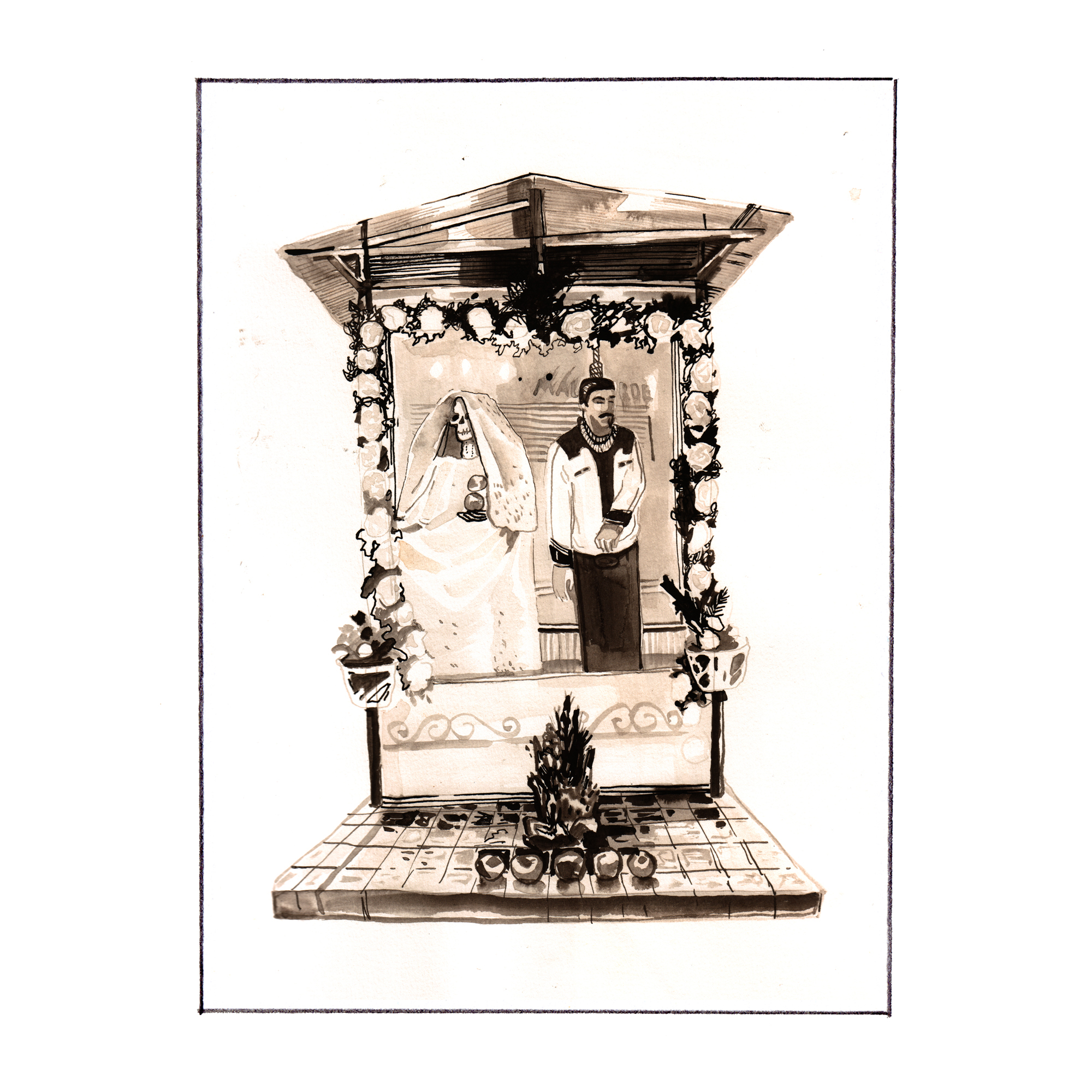

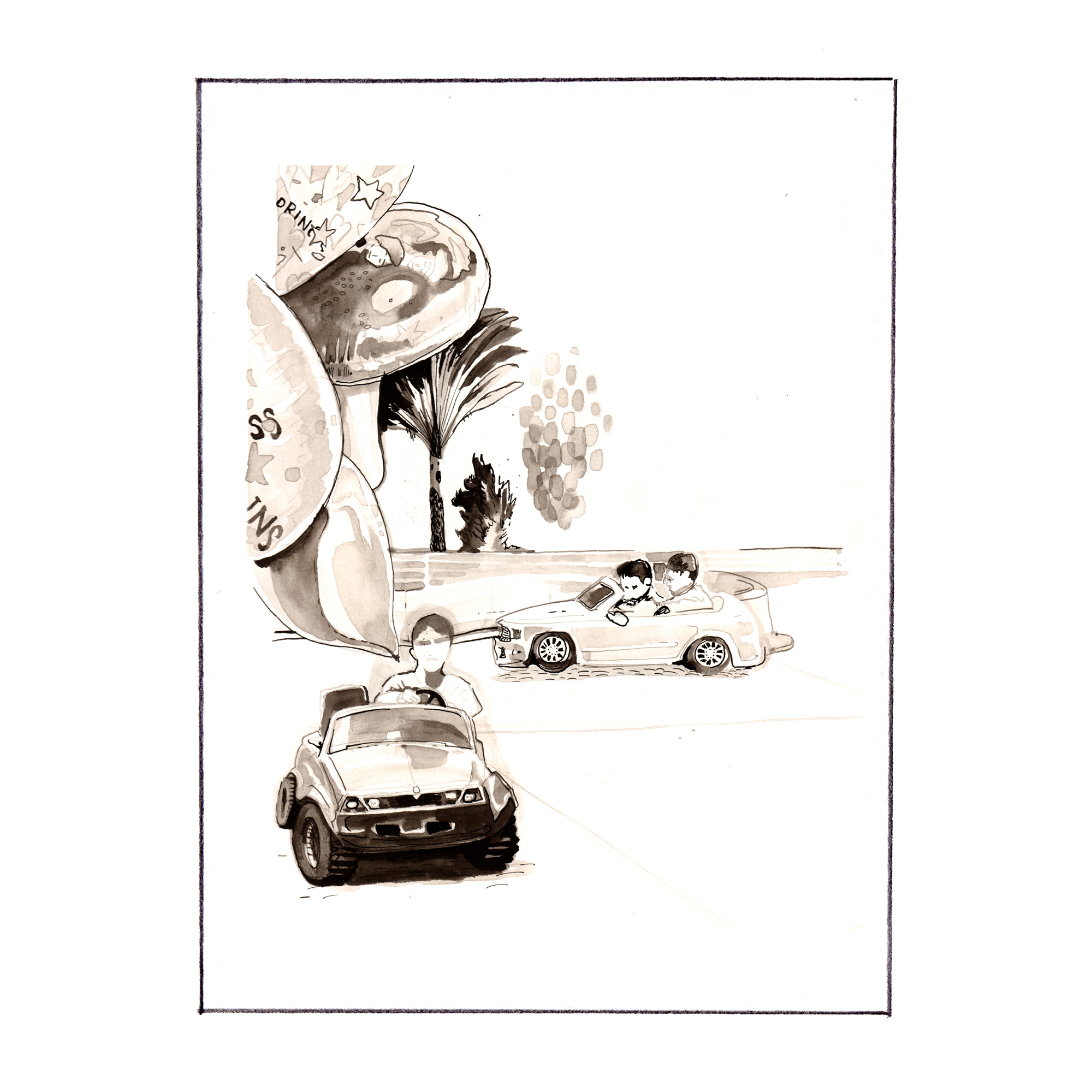

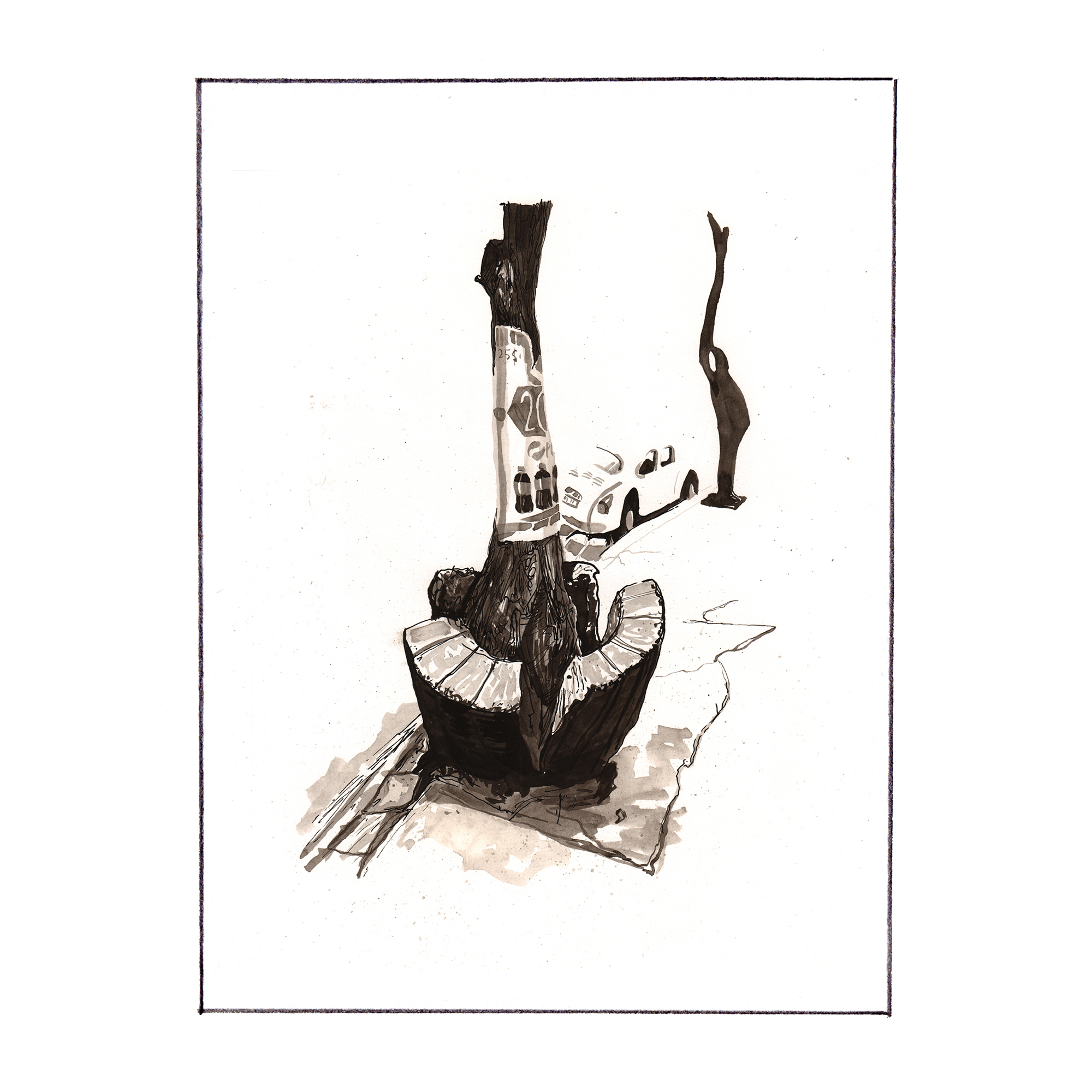

Using sketches, Deelstra documented his observations, creating a sort of diary of the eight months spent with Brahim. Deelstra: ‘By talking to him, spending time together, analyzing his life story, and ultimately painting myself into his world, the gap between us grew smaller, and stigmas disappeared. Although the paintings themselves reinforce stereotypes because, with the images I select and shape, I idealize the world of the other. I have not yet found the most sincere and objective way of connecting.’